Posts in Category: learning

Drawing some Gothic Tracery for carving layout

I’ve always been fascinated with the carving examples of “Gothic Tracery”, and the intricate and delicate feel to them. After taking the “By hand and by eye” class with Jim Tolpin, and the ideas I picked up behind laying out things with a compass, I was somewhat inspired to do a little research. However, there is VERY little out there for the aspiring carver to pick up and learn from.

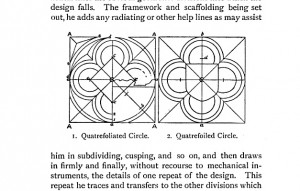

I did finally find a book on Google Books that was of some help: Practical wood-carving: a book for the student, carver, teacher, designer, and architect by Eleanor Rowe. She touches on Gothic Tracery in some what obscure language in the book, and I sat down today to try and figure out how to lay this stuff out.

Starting with this (Page 99)

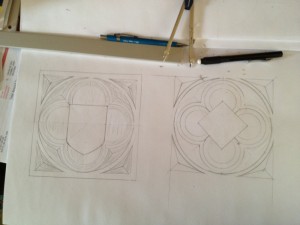

I came up with this:

I learned a few things, and actually feel pretty good about laying out this basic “quatrefoil”. No measuring happened, just arcs and lines. It’s a starting point, and I’m going to try and get some time down in the garage to lay this out, and try some carving.

This one was my favorite of the two, where I used a midpoint on the radius to base the circular lobes on. I know that makes no sense, but putting compass to paper really helped figure this stuff out in my head. The layout was fairly simple once I got started, it’s just complex looking to start out doing.

Let’s see what happens when the chisel hits the wood.

Badger

Question about how to start carving…

In response to my post tonight about my carved tool tote, I got a question about how to start carving similar stuff. The answer I thought might be of more general interest, so I thought I’d post my answer here.

“I was reading your blog post about carving your tool tote. I would like to get started doing some really small and simple carvings. Do you have a book/dvd that you recommend and what are a few needed tools to get started?”

The answer kind of depends on what kind of carving you want to do really, but since the question was about the stuff I have been doing I’ll answer in that regard.

DVD

- Peter Follansbee – 17th Century New England Carving

- Peter Follansbee – 17th Century New England Carving: Carving the S-Scroll

http://www.lie-nielsen.com/catalog.php?grp=1320

Scroll down a bit for the first one, it’s the best for starting out. Then follow up with the S-Scroll dvd. Absolutely top notch stuff, and very easy to understand and learn from.

Blog

Reading Peter’s blog: http://pfollansbee.wordpress.com/ from start to finish. :) That is if you are a geek about history and woodworking like me. Otherwise search on carving.

Books

Tools

I posted a while back about my starter set of tools, based on the recommendations of Peter Follansbee and his basic kit.

https://badgerwoodworks.com/2010/12/peters-carving-tools-interpreted/

this has the list of Tools I started with and how I got the list.

- Pfeil Gouge #9/10 mm

- Pfeil Gouge #6/20 mm

- Pfeil Gouge #8/13 mm

- Pfeil Gouge #8/20 mm

- Pfeil Gouge #5/12 mm

- Pfeil V-Parting Tool #12 8mm

I did about 4-5 fully carved pieces with that set before I started expanding. I’ve added about half dozen chisels so far, but only as I need them for specific projects. The set above is a decent starting place I figure for the kind of carving I do. It’s hard to say specifically what you’ll need since you might have a different design style in mind, but a good V tool and small variety of gouges will be a good as place as any to start.

Here is part of my current kit, which I used nearly off of these for the Tool Tote carving.

Hope that helps.

Badger

My woodworking heroes…

There as a post on the Popular Woodworking blog titled “Who are your woodworking heroes?“ The title gave me pause, because I could think of one quickly but then I was a little more stumped. I had LOTS of heroes, so many it was hard to pick, or worse remember their names because much of what inspires me is the object, not the maker in most cases. I narrowed it down by a criteria of who started me down this crazy journey of hand tool wood-working and making things. I also restricted this list to people alive today, the modern day heroes. I have a couple of historical ones, but I’ll keep it current day for now.

Roy Underhill – Sort of a “Gimme” for this list, but I really can’t say enough good things about this man. I was lucky enough to travel across the country to take a class at his school, and it’s still one of the all time best experiences I’ve had. He is an author, teacher, comedian and entertainer and is genuinely the guy he portrays on TV.   I’ve read all the books, and watched as many of the episodes of Woodwright’s Shop as I can.

Chris Schwarz – I sort of view Chris as the heir to the throne for what Roy has been teaching. He’s taken the cause to heart and is doing an amazing amount to promote and educate on the craft. I like the enthusiasm he shows for it, and the energy he puts into it. Writing books, starting a small press, and educating people. He’s gained a near cult of followers for his troubles, and I really enjoyed his “Anarchists Toolbox” book. One of his editorials in Popular Woodworking about what we could all do to “save woodworking” and said “start a blog!” so I did.

Kari Hultman – I found her blog through another linked blog, and ended up reading the entire thing over the course of a few days. She got me excited about making wooden things, but more importantly gave me the feeling that “Hey, I can do that…” She takes great clear progress shots, and explains just what you need to try it your self.

Peter Follansbee – In addition to woodworking, I have a passion for history. Peter helps combine both, and educates every one who reads his blog on both. It’s inspired me to dig deeper into what I want to do, and helped me learn relief carving quickly. He has a new book coming out, and I’m hoping he will write and write and write.

Carving in Alder

Hope everyone had a great holiday season, and is looking forward to a grand year of hand tool woodworking! I am through the marathon that is my family’s Christmas and Birthday (3) bonanza, and putting my mind towards some woodworking again.

While I was at the Hand Plane Essentials class in Port Townsend we worked in some local Alder wood supplied for the class by the instructors. We were each given a rough sawn plank to work to a finished board through a series of planing techniques. We then took our plank home proudly to show our spouses what we had spent all that money on. :) I also grabbed a couple scraps for testing on carving since it felt like it might be a decent carving wood.

My plank will be come the sides of a toolbox tote I am building, but I did spend a little holiday time testing out the carving tools on the Alder.

Things I learned about Alder wood:

- You need sharp tools (duh).

- It chips out fairly easily.

- It carves really easily.

I discovered pretty quickly that my larger V tool was a little dull. You can see how it crushed the wood fibers, rather than cutting. I pulled out my quite sharp smaller V tool for a similar test and it cut nicely and cleanly. I then did a little gouge work (lower edge) and some low relief work with punched background like I am hoping to do on my toolbox.

I think the test results were encouraging enough to proceed with the carving, although I’m a little nervous about the V tool work. I’m considering a layout that is heavy on the low relief method, and keeping it simple. We’ll see.

Right now I have the sides smoothed, rabbeted on the bottom edge, and sized perfectly. I have a scrap of hardware store 1/2″ thick Oak that will work as the bottom, and I’m probably going to use some Oak for the ends. For the handle I’m thinking of using a little bit of Walnut. Most everything will be carved just so I can get more practice in a variety of woods, and to decorate my toolbox marking it uniquely as mine.

More to come including some thoughts on how to sharpen a V tool.

Badger

Oilstone Sharpening Level Up!

Last weekend at the Hand Plane Essentials class that I took from Port Townsend School of Woodworking, we covered sharpening extensively. they devoted half of the second day to the subject. Unfortunately for me they focused on waterstone sharpening to the exclusion of all other methods, except some on the topic of “sand paper on glass”. This was fine though, because Jim’s system of waterstone sharpening was fast and efficient. I was impressed, but I had previously decided to go Oilstone, and had purchased a number of stones already.

I really didn’t want to switch gears mid stream…

Plus, on the advice of Mr. Schwarz I am going to commit to the Oilstones for a while, and see if I can make it work. If you skip around from system to system you’re essentially wasting time and money. I had purchased a set of India stones Coarse, Medium and Fine. I used some of my bonus money to purchase a high quality stone from Tools for Working Wood.   They just recently started offering a 3″ wide Hard Translucent Arkansas stone in a 1/2″ size at a reason able price. I got the stone in the mail today, and it is a fantastic stone! I was blown away by the quality of this stone. I quickly ran down to the shop (with my three year old in tow, since we were hanging out today) to try it out. I set up the kid with a hammer and some nails and set him loose on some scrap lumber.

I took a Stanley #3 plane I had picked up recently, and gave it a quick whirl using the same techniques that I’d learned at Port Townsend last weekend. With in a very short amount of time, I had a sharp blade and was taking shavings of decent quality. I wasn’t really trying for wispy thin shavings or anything, I just wanted to put a decent edge on it for testing out the new stones. I am very stoked to have finally gotten a sharpening system that I think will show results as I build my skills. My attempts on previous stones that I’d picked up were depressing, but now I know it has to do with the quality of the stones I was using. I’d gotten them at a tool show, with no idea of what I was buying. They’ll be good for knife sharpening I’m sure, but not for plane blades. They are too thin (2″ wide stones) for plane blades anyway.

My Oilstone Sharpening/Honing Method

1x Hard Translucent Arkansas Stone

3 in 1 machine oil

The system I learned at the class was really simple.

1. Establish a bevel at 25 degrees

2. Hone a micro bevel at 30 degrees

It really was that simple. The #3 blade was dished in the middle, and it was pretty dull. In the class we used a grinder and the Lee Valley tool rest (which I have on order) to establish the bevel. On one of my blades we put an 8″ radius for a fore plane blade, but the other was straight across. At home I used the medium India stone to re-work the bevel. The coarseness of the India stone worked pretty well, and I went at it free hand for my first test run. I laid the blade down so the existing bevel was flat, and rocked back and forth keeping the bevel flat against the stone. Soon enough, probably 10-20 strokes the bevel was pretty good, although I think I need to spend a little more time on this blade. I wiped the oil from the stone, and moved to the Hard Translucent Arkansas stone. Adding oil to the stone, I found the bevel, and lifted my hands up an inch or so, and began to rock back and forth again for about 10 strokes. I got a decent micro bevel in that short time, and I hit the burr on the back side with the back flat on the stone, raised by a thin metal ruler (the ruler trick).

Since this was just a test, I popped it into the plane, and ran a few passes over a board advancing the blade a little at a time. Right away I got some good shavings coming off the wood. Next time I go down, I’ll spend a little time setting the plane up, and sharpening some more to practice, but I was pleasantly surprised how quickly I got a decent edge from these two stones. I have some green stropping compound to add to a leather piece I am going to glue to a board for the final polish step.

One thing I want to put into practice was something that I was discussing with Tim Lawson at the class in PT. He talked about honing (strop, or high grit stone) just before and right after you work with a blade will make it so that you will have to sharpen very infrequently because the blade never really gets dull. I’m not sure how that will work in practice, but it makes great sense for my carving tools. I want to set up a sharpening station in my shop, so I can just take the lids off the stones, hone, and go back to work.

I’m not one of those guys who will be obsessing over sharpening, I just want to work the wood with sharp tools, and I think this system (with my new stone) will be just what I need.

Ding! Level up! (Gratuitous video game reference!)

Badger

By Hand and By Eye

I just registered for the class linked above, which I heard about at the Hand Plane Essentials class I took this weekend from Jim Tolpin. It was a great class, and I am really looking forward to this design class.

“Design and Construction Strategies for Hand Tool Woodworkers

This class is based on the research that Jim Tolpin is doing for his forthcoming book with George Walker on the design and layout techniques used in the 17-18th centuries.

These traditional techniques use basic (and simple) geometric techniques to create designs for well proportioned furniture. The notion of well proportioned is ingrained in the human eye and is rooted in the different elements of the piece of furniture having whole number proportions (like 1:3 or 3:5).Â

These proportioned dimensions are easy to create using a sector and dividers. A sector is a simple tool made of two sticks hinged together (you’ll make one in class).

You can, in fact, create a whole design with out needing to reduce the dimensions to feet and inches (or millimetres)! This can be liberating for the hand tool woodworker – it can help you escape the tyranny of the machine or getting overwhelmed trying to use a drawing program on your computer.

Jim also looks at how your design and layout of joinery should be slaved to your tools. Making simple decisions during this stage can greatly simplify the process of dimensioning the stock and cutting the joinery.“

We were discussing this on Sunday as the class was winding down, about the difference between the engineer perspective and the artisan perspective. I made a comment that I really liked. “Measuring is so imprecise!“  It really is, when you are talking about woodworking, you spend a lot of time get a measurement dead one, and the saw drifts a tiny bit, and you’re short. That is if, you’re cutting all the pieces in one go. If you cut one piece, and then fit it to the next, and then base the next off that, etc. you will be guaranteed to have it fitting right. This is how the artisans who built all the furniture we love to emulate, and are inspired by. At best they had a two fold rule, no digital calipers, or table saws. I am super excited about this class and the book that follows the research they did coming out at Lost Art Press.

Badger

Training a young apprentice

It’s been a really brutal month at work, and I haven’t had ANY time to get into the garage. However, the Thanksgiving holiday is upon us, and I finally have a little time off. While at the local Harbor Freight store picking up some extra dividers, and a set of number stamps I saw a Kids Tool kit for like $15 and had to have it. The only really useful thing in the kit was a small hammer, but the hat goggles, and suspenders were fun for him to play with.

This lead me to something I’d been thinking about for a while, how to do teach my kiddo how to work the wood, and when to start. I’ve decided to start now, even though he’s not even four yet. I’m going to start by teaching him a tool at a time, like a true apprentice. The first project will be a small tool tote in Pine for him. I’ll do the cutting and stuff, but he is going to do the nailing part. And he’ll get a hammer to put into it. After that we can work on sawing, and other tasks.

Badger

Rules for Work from the Boys Own Workshop.

The boy’s own workshop – Jacob Abbott – Google Books.

Discussion about this book is making the rounds of the blogs right now, and I wanted to call it out as well. I read this on my Kindle while on vacation and it was a great read, that I learned some fun stuff about hand tool woodworking, and more to the point I learned some things about how to approach the craft as well. I highly recommend reading this book, and if I had any idea how to do it I would reprint this book in a nice bound format to put on my shelf next to my Lost Art books.

“Rules for Work

It was late on Saturday afternoon when the boys completed the work of procuring and laying in their stock and their tools; and several days elapsed after this before John had an opportunity to commence his work. Ebenezer advised him, if he really wished to learn to do anything with tools, to consider it work, and not play; and not to undertake any operations until he had ample time for them, and then to proceed step by step, in the most deliberate and cautious manner. He must never act in a hurry, he said, in order to finish something at a particular time, or attempt to work with a tool that was dull or out of order, or to use a poor or unsuitable piece of wood because he had no proper piece at hand. Such management as that, Ebenezer said, only led to disappointment, worrying, vexation, and failure. “Â — Boy’s Own Workshop by Jacob Abbot

I am interpreting this as the following Rules for Work:

1. Work Deliberately. I tend to rush when I get close to the end of a project. And usually screw things up by doing something stupid. Now I am taking the time to think through each step, and find the simplest solution, not the first thing that comes to mind.

2. Use the right tool for the job. Sometimes when I rush, I’ll grab whatever is handy and try to force it work the way I want, and sometimes this ends badly.

3. Work with Sharp Tools. I sometimes want to get right to work, but I’m making myself stop and make sure my tools are ready to go before I start. Even if this means that is all I get to that night in the shop.

4. Work in discrete chunks. I am trying to work in stages, and only tackle a project that I can finish in the time I have. This way I feel successful at the end of each section, and I start each session with a starting point and an end point.

I’m still working on these rules, and feeling out how it works in the shop, but I feel good about this so far. Work Deliberately seems to be encompass a lot of the idea. My first project with these rules in mind went much better than previous ones. The end result just simple felt better, and I felt like I actually knew what I was doing. It’s a good feeling.

Badger

Quick Stock Removal Tip – Drawknife

I’m thinking of starting a regular feature on this blog called “things I learned in the shop” because it feels like every time I go down there I feel like I learn something new. Which is part of why I do this stuff, I love to keep pushing and challenging myself.

I had to trim the bottom of my sliding tray drawer for the Saw Bench Box about a half inch. I thought I could just set my Jack up for a heavy cut, and plane it down quick like. But I soon discovered it was taking way too long. On a lark I reached for a drawknife that I had purchased ages ago and hung on my wall waiting for an appropriate moment to use it. I started pulling along the edge of my board that I had marked with my cutting gauge on all sides (this is important) and the wood came off in very thick shavings, I’m talking 1/4″ or more at a time. It is important to pay attention to the grain (when is it not) because it could easily dive down under my cut line if not careful and grain was not straight.

When I neared my cut line, it actually split along my cut on both sides. It took only a few moments to pare down the waste, and a few passes with my bevel up Jack plane to lower the high spots. Speaking of Bevel Up, I was using the drawknife in the mode, instead of bevel down. It worked really well, and I think I might use this again before reaching for a saw. Which is ironic because this is a sliding tray for my Saw Box.

Badger

A few thoughts on nails

** EDITED POST – Added link to TFWW Nail Shop **

Recently there have been a few posts around the the blogo-sphere, the best being on the ever fantastic blog Village Carpenter, about the WIA class on nailed furniture. I recently had a similar revelation in my shop while working on my “Anarchist’s Saw Bench Box” (more on this later) about the use of nails.

I had spent an entire evening of my precious time wresting with a series of doweled joints for the side of the box, and was prepping for doing the same thing for the bottom of the box. It struck me then, that all the effort and wrestling and balancing of the boards didn’t seem very efficient. What would have my theoretical counter part have done in my stead?

He would have nailed the damn thing down and have done with it.

I think we tend to over-complicate, and over-analyze the methods of work they used, and focus entirely too much on the show piece joints. The fascination with dovetails leads us to use them in places that are more than is needed. People spend hours and volumes of words debating angles, and tails vs. pins when our craft ancestors would have just done the quickest method and moved on. And don’t even go anywhere near sharpening!

So, some thoughts on nails…

The first project in the The Joiner and Cabinet Maker is a simple nailed box. No dovetails, or fancy joints, just a simple nailed box done with care and pride. Dovetails ARE an appropriate and beautiful joint, and I fully intend to make many a piece with them, but do they belong on every thing? Sometimes a simple rabbet joint, and a few nails is all you need.

I’ve used a couple different kinds of more or less period nails lately and enjoyed the look of them, and the ease of use.

The wrought head nails from Rockler work quite well, and the look of the box after completion was great. I loved the look of them, and have been using them more and more. The shaft is not perfectly smooth, which gives it a bit more grip.

The Tremont Nail Company is still making nails the old way. They are bit more expensive than your ordinary hardware store nails, but they give the work a bit of panache that would be missing with an ordinary nail, as well as the ability to “clinch” a nail through the wood for greater holding power.

There is one small note of caution though on the use of these nails. You can’t simply poke them into the wood and hammer away freely, because you’ll likely end up splitting the wood. The shape of these nails is more of a wedge generally, and can force the wood apart. You need to dig into the past a little to complete the picture. To prevent splitting you’ll need to open up a small hole first all the way through the wood with a tool of some kind.

There are a couple different ways to do this, one of which I’ve been experimenting with lately is the use of a “brad-awl” which looks like a small flat bladed screwdriver and is driven into the wood with a twisting back and forth motion to open up a hole. When done right it doesn’t so much as drill a hole as move the wood fibers to the sides. This allows the fibers to grab the nail as they are driven into the hole. This works best in softwoods like Pine as far as I can tell from my experimentation. In hardwoods like Oak, I’ve found that “birdcage awl” or a gimlet bit works best to make a hole through the wood.

I’ve made my own from regular scratch awl blades I picked up at HF, and cut the two flat facets on the blade on the grinder.  I initially made my angles way to steep and the metal bent and twist at the tip because it was too weak. I’ve been experimenting on a broader angles to good success. To make a “birdcage awl” I ground a four sided pyramid shape into the tip of another scratch awl (I bought a handful of these things for cheap) and it works wonders on Oak with a simple twisting motion. I can get a hole through a 1/2″ board quicker than I could have found my bits and got it chucked up in the cordless drill (which is usually out of juice most of the time anyway). For multiple holes, it can be a pain, but for a few holes it’s super easy and quick.

And finally, I leave you with a link to an article I found on the net titled “Forged and Cut Iron Nails” by Gregory LeFever.

— Badger

P.S. Tools for Working Wood has opened up a new “Nail Salon” on their site, selling Tremont Nails in small lots, which is a good idea to order a few different kinds to experiment with.

You must be logged in to post a comment.