Posts in Category: learning

Scroll panel Layout example

I was contemplating the S Scroll carving that I had recently finished, and looking forward to trying a different technique on the next set. The question in my head was, do you do the outline with ALL chisels, all V-Tool work, or a combination of both. The answer according to Peter Follansbee is “All of the Above”. I did the most recent panel with all chisel outlining only. I’m going to do the next panel with V-tool outlining with some chisel work to outline the leaves. I also had a couple of lingering questions on how much layout did I do to before starting, and how much is free hand, etc. etc.

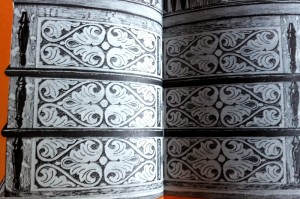

Checking on PF’s blog he posted just recently about tool marks present on extant 17th pieces. He did a close up of some marks on a Scrolled panel like I’m working on figuring out. It showed some marks left visible from whatever craftsman made it the first place, which helped me understand some of the layout tricks they used.

I did some work with a Paint program to highlight some of the visible marks. I also modified the original image with “emboss” filter to show the lines better, which accentuates the V tool lines.

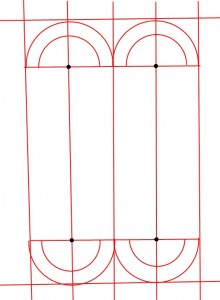

Then I took the background away to show just what the layout lines would look like when starting from scratch.

Which makes it much easier to understand the starting point of the design. You layout just this part, and you can probably do the rest of the design with just tools with a little practice. I found that to be true after only four of the Scrolls on my previous panel, and I could see how after you do a bunch of them it would become second nature. The half-circles would make it easier for the whole design to be visually consistent, especially if you were doing a whole bunch of these in a row. You could do all the similar markings on one setting of the compass, and then set the smaller diameter and do them all in a row.

Remember these were production houses and working gentlemen making these, and if it was easy to repeat and you could get more efficient with a few tricks, then they probably did it.  I’m looking forward to trying this on my next panel…

Badger

More Scroll work and my new Carving Bench

I snuck down to the shop after I got my kiddo to sleep to continue work on the S Scroll box face. I got a second scroll complete, and some of the outline of the other two. I’ve also learned a few things about crappy hardware store wood along the way. The open porous grain of this oak causes some serious issues when carving, and it’s difficult to get a nice clean surface (not flat, just clean) because the would just disintegrates as I try to carve it out. It also is weaker than the solid parts (fairly obvious really) and causes some splintering on the areas where it shouldn’t. I’ll have to fix those later once I’ve gotten this all done, or maybe I can plane it down, not sure.

I did modify the design here and there to accommodate sections of weakness to good effect, but I have a couple spots that are going to be a problem. I see a little more clearly now though why some of the designs I’ve looked at, and PF has discussed as well are not totally symmetrical.

I also am learning a lot about what I need to learn. Sounds awkward, but it means I’ve learning some of the things that I will have to simply practice a lot to get better at. You can feel it when it works right, it just… Makes Sense. In a Zen sort of way, it feels right. And the converse is true. You can really feel it when it’s not at all right. I’m trying to learn to take a deep breath, slow down and think those areas through rather than my natural reaction which is to panic and push harder or move faster. Which usually doesn’t work so well, as you might imagine.

I also snapped a picture of my new “carving bench” or maybe it’s a “bench on a bench” or something. I’ve seen a few blog posts around the woodworking blogs about these, and I decided it was probably the best thing for my aching back after a long session of carving. Night and Day! I just screwed together some pieces of left over construction grade lumber, and clamped it between the bench dogs and vice to hold it down. Nothing fancy either to hold the work. I have visions of using some of those fancy Wonder Dogs, or whatever they call them from Lee Valley, but that was too complicated and I didn’t have them anyway. Clamps work great and the board is not going anywhere.

Off to bed, with visions of S Scrolls dancing in my head.

Badger

Practicing S Scroll for carving

Example of S Scrolls on 17th Century Furniture. Original Cupboard is at Yale University, made in New Haven or Guilford CT c. 1640-1680. Image from “Treasury of American Design and Antiques – Clarence Hornungâ€.

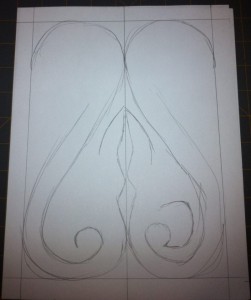

Today I spent some time practicing a bit of carving… with a pencil. I recently read in a book recommended by The Village Carpenter (Kari Hultman) on her blog. I’ve been reading it since I got into the hand tool woodworking, and it’s been an inspiration. The book “How to Carve Wood” by Richard Butz recommended practicing some of the carving details on paper before putting chisel to wood, and I’ve been wanting to try some of the S Scroll type carving in the near future. So I set out to try it today, and now that I have I highly recommend this practice for figuring out complex patterns. I’ve been staring at the S Scrolls on period pieces, and it’s a bit hard to figure out where to start. I know the theory, but the practice sort of intimidated me.

So I started out by laying out the layout lines I would use on the wood.

Then I made rough half circles for the tops of the S, which in the wood I would probably do with a pair of dividers.

Next I extend the middle of the S lines in a diagonal fashion, forming the middle of the S, paying attention to the thickness of the line I am forming.

Once I’ve formed the S, I then start working on the floral inspired stuff that fills the space. I found it very helpful to take the bottom of the S and form a small circle, and extend that into a leaf to fill some of the space in the bottom loop. Same with the side leaves, extending up the middle guide lines with some curves that will become leaf shapes.

Next I bring the leaf shapes of the middle, and bottom and fill in two leaf shapes between them, trying to form them using shapes of a chisel, since that is how I’ll outline these. Then I just did the same thing up sides with the top leaves. The basic outline is done at this point. It helps to look at the negative space, to see how much is left, since you’ll have to carve this away. Keeping it even is good too, but not totally required.

Next I add some “veining” that I would do with the V tool, and play with some of the open space, to see if maybe leaving some moon shapes would look good. It’s pretty free form at this point.

That’s pretty much a complete S scroll pattern. It can be repeated endlessly, and it can be scaled up or down to fit nearly any rectangle shape. You find them with back to back S scrolls like I did here, or you see them as a single S alternating as a border. I spent a few pieces of paper getting some of these sketched out, and I feel a lot more confident setting chisel to wood now. I’m sure it won’t be as simple as sketching, but at least I now have a concept of how to lay it out.

My next step is to apply this treatment to some Oak I’m going to turn into a saw box.

Badger

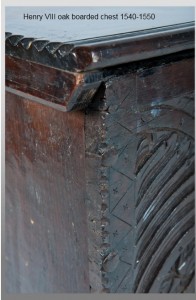

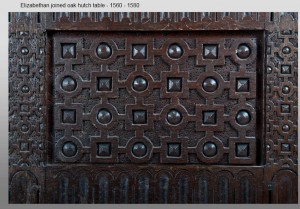

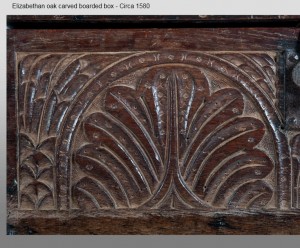

More on punches with examples

I’ve been scanning the internet for examples of the punch marks used in period carving work. And when I say the Internet, I really mean Marham Church Antiques, and Peter Follansbee’s Blog. If you’re in to 16th – 17th century woodworking and carving then both of those sites should be in your favorites. The first on is not a wood working site per se, but it’s filled with wonderful pictures of antique wood chests, furniture and more. It’s well worth a browse for inspiration, carving patterns, and if you’ve got extra money you can purchase some of them. I’ve been tempted on a few occasions, but we have a big travel vacation planned this summer that I need to save for. Peter’s blog I’ve gone on and on about, so I won’t reprise that.

I was able to find a nice set of punched decorative marks on the Marham site, and I’ll show them here. My next step is to make a set of these, so watch for that post later. I’ll be documenting my steps as I go, so hopefully that will help out a little.

The last two are from Peter’s Blog, and the rest are all from the Marham Antiques site. The last one has THREE different punches used in the decoration. I’ve been using a nail set as a small circle punch in my carving so far, and it’s super easy. I’ll be posting the finished box later, which shows two different punches used, the nail set, and a nail I carved into a cross pattern with small needle files.

Once you start looking for them, you can find them in all kinds of places. Once you start using them, it’s hard to stop. It’s a simple way to add a little flair to your carving, and just as “nature abhors a vacuum” so does 17th century carving. I’ve noticed that the carvings generally have very little in the way of flat open blank space.

Badger

Carving layout trick

Tonight I started work on another version of the carving layout from last time. I was setting up to measure out the layout, and happened on a method of laying out perfect squares with no measuring. The 17th century layout that I’m using, is based on squares, and my first attempt was a little off because my measuring wasn’t perfect. This trick worked great, and my squares were right on.

Here is the finished layout, with the tools I used to accomplish this.

Steps:

1. Using a marking gauge, layout a border along the top and bottom of the board along the long edge.

2. Using the compass starting at one end along one of the edge lines, figure out the middle point. I just keep switching back and forth between the ends moving it a little each time until the arms of the compass are at the same point from both ends.

3. Using a square draw a line down the mid point line across both edge lines.

4. Put your compass in the point where the mid point and top edge line meet, and spread the arms to the opposite point on the bottom.

5. Make an arc lightly on both sides, and repeat from the bottom point.

6. The point where the two arcs cross is the middle length line, and you can mark this line with a straight edge through both points.

7. Now put the compass arms to the top mid point, and the point where the middle lines meet. This is the size of your squares.

8. Pace out points along the top line, using the width you found in step seven, and mark lines from each of these points with the square again.

Ta Da! You have a square layout, no measuring, and you didn’t have to do any complicated math to figure out the size of the squares. Now it does help to measure out some rough idea of what you want to make sure you cut the wood to the right size, but I leave a little on each end to trim down later.

The first time I tried doing the squares, I spent a lot of time trying to find the right size for the squares, dividing and fudging, and in the end my measurements were off a little bit. This way I can make it close enough in length, and just pace out the squares based on initial measurement (the top and bottom edge setting on the marking gauge).

My first 17th century carving attempt

The last month or so has been a whirlwind of stress at work, as well as being very cold in the shop so I haven’t been able to get down there as much as I wanted. But finally I got a little time to work on this carving that I wanted to work on since I got my Peter Follansbee set of carving chisels. I’d been admiring this particular pattern on a 17th century box he’d posted in his blog a few times, and I thought it might be a good place to start working from. The reason I chose it to start was because it was mostly V tool work, and I could visualize almost every step in my head. Plus it looks very cool, which is always a plus. I’m going to be making a bible box in the near future as a present, and this was one thought for the carving I wanted to add to the box. So, I cut up some flatsawn Oak stock and gave it a whirl, and it came out pretty good for my first attempt really even if I can’t get any riven partially green stock like PF uses.

To achieve this carving, I started with a simple grid layout of 3″ squares centered on the front. I did multiple sketches on paper first to work out the details, and this was the easiest way to start the layout process. Once I had the grid lightly marked into the wood, I got out the compass and made a series of arcs along the top and bottom rows, alternating the starting points to get them offset. I made one big mistake here, and didn’t count out the grid exactly right and as such, my design was short one set of arcs/grid squares, but it works out because the design looks good on any number of repeats.

Once I had my first set of arcs down (I penciled them in above to make them clearer in the photo) I eyeballed a good looking distance and carved another set of arcs inside the first set of arcs.  This could have been a little bigger I think, but overall it didn’t look too bad to my eye.

And that was the extent of the actual layout for this design.  I did most of the rest of the design freehand with what looked good, trying to follow with traditional carving techniques as I’ve learned of then in PF’s blog. He shows numerous examples of symmetry being off for our modern eyes and numerous things we would call “mistakes”. Once you look at it as a whole though, it all looks good. The major mistakes I made doing this were the bottom U shaped cuts, I need to actually lay those out next time, as going from either side was difficult to reproduce, and my half moons in the lower arc were chipping out a lot which could be wood, or technique issues.

But overall, for a first practice piece I felt pretty good about it, and it was good to finally get to practice what I’d been reading about on PF’s Blog, and watching his DVD.

Badger

How to cut a dado using hand tools.

Cutting a dado

When I set out to the dado for the train rack project, I sat down with the internet and browsed a few books. It took longer than I wanted to find a method using no power tools. Cutting a dado slot is most frequently done by table saw if you believed the internet. I didn’t want to use my table saw, besides, I don’t have a stacked set of a dado blades either. I finally found what I was looking for in the Tomes of Saint Roy, and I set out to do this my self. It turned out to be as easy as he said it would be. And I was able to get a nice crisp line slot cut quickly without having to use my noisy, and to be honest a little scary, table saw. Here is how I cut my first dado slots by hand.

Marking the Board

The first step is to mark all the important lines you’ll need to make your dados clean and even. Take a marking gauge and mark the long side with the depth the dados should be. Then take your take your square and mark out the lines where the dado’s will go. Plan this part carefully, and take your time laying the lines out and will show in the final work.

It really helps to have your work secure as you start this, but it could be done on a bench hook if you don’t have an end vise and bench dogs set up. Once you have your line drawn in a light pencil mark, take a marking knife to follow that line with a shallow cut. It helps to hold the square firmly, and keep the knife pressed against the edge of the square, and the handle straight up and down from the board. First pass should be a light cut, focused on keeping it straight and true. Subsequent cuts should follow this line, going deeper each pass until you have a nice deep cut. The goal is to sever the fibers, and make a square straight line with a clean edge. If you just cut straight on the pencil line with a saw you’ll likely end up with frayed or rough edges. Now is a good time to mark the waste side as well, just like in dovetailing, so you can keep your cuts on the correct side of the line.

Cutting the V

Once you’ve got a good cut line in the board, you take your knife and cut a sort of V groove on waste side of the line.  Make sure to not undercut your straight side, and keep the cuts in the waste side of the line. It doesn’t have to be super straight, since you’ll be getting rid of this material anyway. You’re going to create a trough for the saw to ride in, which will make your cut go straight and keep it riding where you want it to. It’s too easy for a saw to skip when you’re starting your first cut which can lead to ugly edges where it might show on your finished piece. I also find it helpful to cut an extra notch with my knife where the saw cut would start to prevent any chance of skipping, just make sure to only notch the waste side, otherwise it will show.

Sawing the line

Now that we have a trough for the saw to ride in, it’s time to cut the line down to our marked depth. I’m using a vintage Disston back saw that I picked up at an antique store and rehabbed for this, but any clean cutting saw should do as long as the kerf isn’t too wide. Take the saw and rest it in your groove, and carefully start your cut. Keep an eye on the cut and make sure it’s on track and it’s not jumping around scarring the work. Once you have a good cut going, you can pick up the pace a little, just keep good control in mind. Check frequently on both sides to make sure you are not cutting below your marked depth. It doesn’t take long to get to the depth usually, since the dado is probably not too deep. Make sure you’re right up to the depth line on both sides, and stop.

Make the second cut

Now we should be ready to cut the second line, but first it’s a good idea to double check your width by holding your shelf board to the line, and seeing if you need to adjust it any. I had been sloppy in marking my lines the first time, so you can see second pencil line in the photo. Sizing from the actual board is a good way to eliminate any measuring mistakes. Repeat the steps for cutting the first line with the marking knife, but be this time be sure to cut your V on the other side of the line, keeping it in the waste as always. After cutting a good V, saw down to the line as before.

Chisel out the waste

Now it’s time to start making the actual dado after all that measuring, marking and and cutting. Take a chisel as close to the width of your dado as possible, or smaller if you don’t have close, and begin to chisel out the waste. I like to start on each side with a quick tap a third to half way from the top to prevent tear out. Don’t try and hog the whole thing out at once, just take a couple layers out first. Go easy for the first third to create the walls, and then you can be a little more aggressive. Once you’re into it, I liked laying it bevel up and holding it flat and pushing it horizontally to peel up the bulk of the waste, but use whatever chisel technique you’re comfortable with. If you’re going to use a router plane to finish, then don’t go all the way to the bottom of you cut, leave it a little proud. Otherwise, pare down the wood as smooth as you can.

Finish the bottom of the cut

I used a Stanley #71 to finish out the dado bottom to ensure a clean tight fit. I set the depth at just shy of the marked line for the first couple of passes to avoid tearing out too much, but it went really quickly and I had a nice clean trough in no time. A final pass at the marked depth, and I was done and had a clean edged dado.

Final Thoughts

This took a lot less time than I thought it would, and once I had the technique down (and took lots of photos) on the first board, I was able to assembly line the second board in half the time. The project was well recieved by my “client” aka my 3 year old son, who got a sweet new rack for his growing Thomas Train collection.

A mystery solved

A while back I posted about a odd looking plane I’d found in an old painting by Jacopo from 1574. Recently I posted about a painting of building the Ark by Kaspar Memberger the Elder that had some great shots of workmen and tools. Yesterday I found another painting by Jacopo that I hadn’t seen before that showed nearly the same exact scene that Kaspar had painted, but with different tools. One of the paintings is a copy of the other for sure, but I wasn’t able to find much on the painting itself. The newly discovered Jacopo painting looks like it had been damaged either by cutting or folding, which might explain why it’s much less popular than the other ark painting he did.

The really cool thing about this new painting though, is that it shows one of the workmen clearly demonstrating how that strange looking plane with the roman style handle in front of the blade, rather than behind, is used. The fellow is clearly pulling the plane! And there are a couple other planes in the foreground as well.

It’s a little mystery solved, phew! It’s odd though, most European planes were designed to be pushed. The roman style handles are very rarely found due to ravages of time, but there are few examples still around due to volcanic action (Pompeii has a few). The cut out style was seen in the known examples as both ends of the plane, or behind the iron as seen below in these scans from Goodmans book on History of Woodworking Tools.

Interesting stuff. One of these days I’d love to make a reconstruction of these planes to see how they work, but I think I have a few more challenges to get through first.

Badger

A 1510 Joiners Tool Set

Details on Painting:

Artist: Jean Bourdichon b. 1457, d. 1521 Tours, France

Title: The Four Social Conditions- Work

Date of painting: 1510 (from “The history of woodworking tools” by W. L Goodman)

I ran across this great picture of a painting dated to 1510 of a Joiner in his workshop. I love these old pictures, because you can get a glimpse of the work and tools from a distant past.

A lot of discussion has happened about tools and work from the 17th century, due to a number of excellent books available in reprint these days, but there really isn’t a lot of resources available for pre-1600’s woodworking.

Here is one of the rare instances that I’ve seen that shows things so very clearly. It also shows a snapshot of life back then. The child on the floor collecting shavings for use in the fireplace presumably, the wife working on something, maybe weaving? But for me the really great part is the tools.

You can clearly see the following tools:

- Jointer or Try Plane

- Smoothing Plane

- Chisels of several types

- Mallet

- Square

- Compass

- Small axe

- Bowsaw

- Piercer or Brace

That’s a pretty solid set of tools. In the foreground you can see a linenfold carved chest, and the background you can see a gothic style carved chest. What little research I’ve done on this time period says that this is the transition period between those two styles of carving.

Interesting stuff.

Badger

Trying a little carving

I recently purchased the DVD of Peter Follansbee and his lessons on 17th Century Carving. I’ve been a huge fan of Peter’s blog for a long time, and so this was a no brainer. I also picked up a V-tool to try the first basic lessons. I got a little time last night, and I decided to give it a go. No planning, no good wood, just what the heck, pick up a piece of scrap and go at it. Results pictured above are pretty shaky, but I can see how it works now. It’s putting to practice what I’ve been reading about, and it’s always different when you actually try it. I want to get some better wood (crappy pine board is not going to do me much good really, although I could add some carved decoration to some boxes if I am careful, and use simple designs.

Note on the tools pictured:

- Home made Applewood mallet

- Woodcraft purchased V tool

- Harbor Freight purchased compass

The compass was recently discussed here on Peter’s Blog, and I dug out the couple of dividers I picked up for cheap at Harbor Freight the other day. I never really used them because I didn’t like the pencil holder, it just got in the way. Tonight I clamped the pencil ring into my metal vise and just levered it off. It popped off easily, and there was a little bit of weld residue left, but otherwise it was clean. It became much more useful that way, because I could grab it with both hands and walk it around.

I tried some gouge work but that was more fail than anything else. I’m really not sure what the gouges I’ve got are. Are they carving gouges? or firmer’s gouges? I’m just not sure. I also spent some time learning to sharpen them on my new stones, and that went better than I expected. I got a reasonable (not quite decent edge) despite not having a clue what I was doing. I’ll have to study a little more to learn a little more technique. That’s how I learn. Read. Try it. Read again. Try it again. Eventually I’ll either get it, or give up.

If any one has any knowledge on Chisels, and can help me identify the chisels pictured, that would be most excellent. Can I use these for carving? My results were mixed even after sharpening.

Badger

You must be logged in to post a comment.